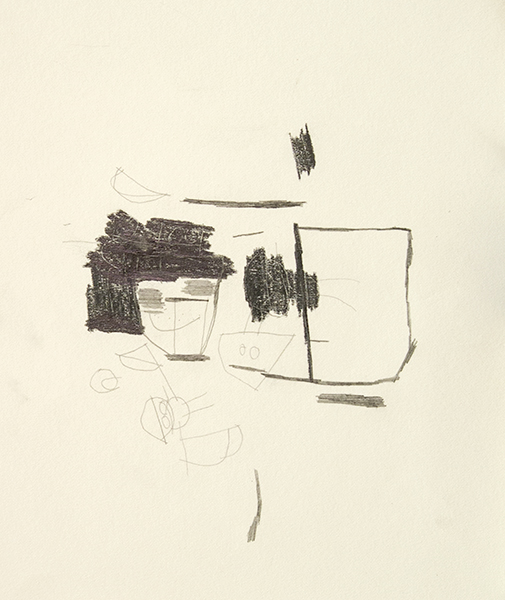

My Body, mixed media on canvas, 18" x 24", 2015

Jed Clampett, glazed ceramic, 10" x 7" x 4"

Untitled, acrylic, 18" x 24", 2015

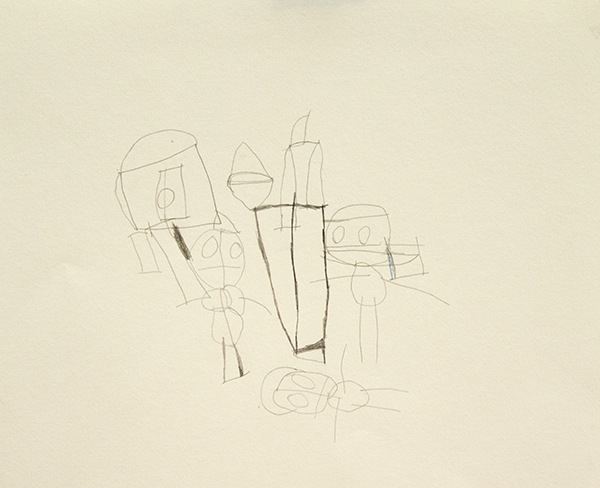

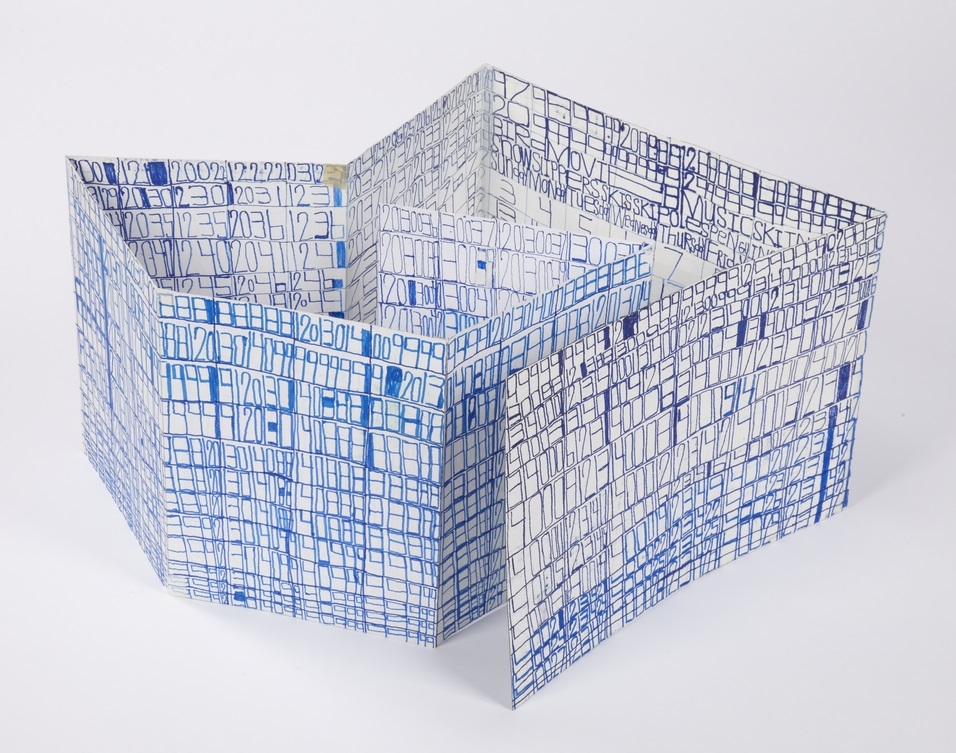

Untitled, graphite on paper, 12" x 17"

Untitled, mixed media on canvas, 24" x 18"

The process of evaluating any artwork includes some interpretation of how it functions - mechanisms such as the way gestural brushstrokes communicate movement by indexing the physical action of their application, or the way that arrangements of representational imagery can imply relationships between elements that generate narrative.

The mechanism by which Billy White’s paintings elicit emotion is sharply specific, yet escapes analysis, remaining a wonderful mystery. A loose, fearless application of paint renders forms with a striking physicality and sense of humor. There’s an uncanny affinity with the work of figurative painters Todd Bienvenu and Katherine Bradford (who both have an aesthetic undoubtedly informed by the work of self-taught artists). The impact of White’s work cuts through a vivid alternate world that operates on White’s terms - a highly original set of priorities, passing over image and rendering to achieve an expression of mood and vitality, as though excavating the underlying stories that were already present; impatient mark-making and barely legible imagery find time and space for redolent storytelling and detail. While he typically focuses on painting and drawing, White occasionally creates small ceramic sculptures that are rich in character and evocative of Allison Schulnik’s warped clay figures - slumped postures, elongated, rubbery appendages, intermingling glazes, and sunken, cartoonish expressions.

White’s work is largely influenced by his avid interest in pop culture, often depicting actual and imagined events in the lives of various celebrities or fictional characters, from Dr Dre to Hulk Hogan to Superman. NIAD provides some insight into White’s process: “He might start off painting Bill Cosby, but quickly change his mind by lunch. When that happens, he simply works right on top and doesn’t erase what came before. The new work becomes an extension of the old. By the end of the day this could happen several times and what’s often left is a latticework of figures and stories with interchangeable meanings.”

Billy White (b. 1962) has exhibited previously in Rollergate at the Seattle Art Fair, Telling It Slant organized by Courtney Eldridge at the Richmond Art Center, Undercover Geniuses organized by Jan Moore at the Petaluma Art Center, ArtPad San Francisco at the Phoenix Hotel, and extensively at NIAD Art Center, where he has maintained a studio practice since 1994. He has an upcoming solo exhibition at San Francisco’s Jack Fischer Gallery later this year.