Throughout 2015, Disparate Minds writers Tim Ortiz and Andreana Donahue worked directly with The Canvas, a progressive art studio in Juneau, Alaska as Artists-In-Residence, guest facilitators, and curators of the group exhibition NEW VOICES.

Mike Godkin, Transportation: boat, plane, car, chalk pastel on vellum, 12" x 12", 2015

Jeff Larabee, Untitled, sharpie and marker on clayboard, 16" x 20", 2015

Mirov Menefee, Untitled, ceramic, dimensions variable, 2015

Mirov Menefee, Untitled, colored pencil, graphite, and micron on paper, 18" x 24", 2015

The Canvas is a relatively young studio and when we initially joined them was beginning to transition from a didactic approach to art-making to one of professional development. We were given the opportunity work directly with artists in the studio alongside facilitators to share ideas and knowledge about further developing the emerging creative culture and cultivating an environment conducive to the independent discovery of art-making - guiding artists to invent and maintain studio practices of their own devising. We focused on post hoc guidance through the introduction of criticism in one-on-one discussion and group critique, challenging artists to explore the potential investment of time and care available in each of their processes.

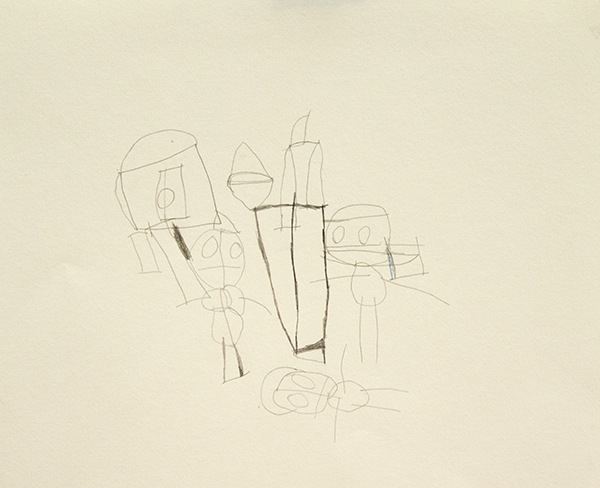

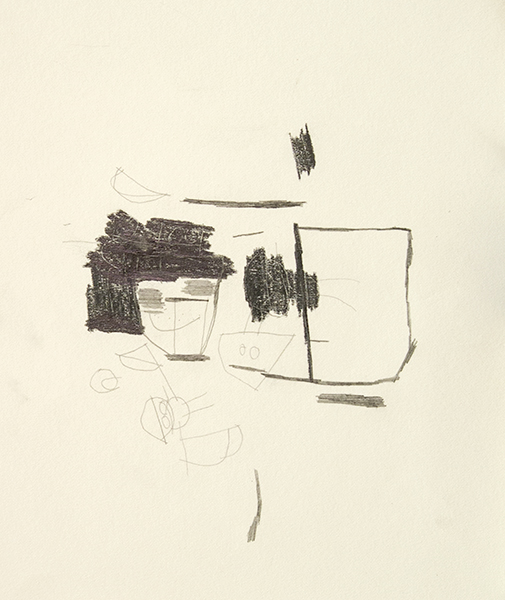

The result of this paradigm shift has been a wealth of inspired new ideas and creative voices. NEW VOICES represents a selection of current work in various media by this studio’s most promising and successful artists, including many that we’ve discussed in essays for Disparate Minds over the past year: the nuanced minimalism of Grace Coenraad, Luis Hernandez’s intuitive yet complex abstractions, the enigmatic text-based drawings of Jeff Larabee, and Susy Martin’s bold, layered symbolism. This exhibition establishes a dialogue between artists and artwork, accentuating similar investigations of visual language and innate tendencies - repetitive processes or subject matter choices, surface manipulation, emblematic mark-making, or heightened attention to detail.

Other highlights from the exhibition include:

Mark Davis, Untitled, colored pencil on paper, 19" x 24", 2015

Mark Davis’ first major work on paper - a complex, pattern-based drawing in colored pencil, created using an intuitive set of rules, built methodically from bottom to top; it’s a spectacle of fluorescent color and rich detail, paradoxically both a simple, flat pattern and organic rendering of form reminiscent of a woven textile.

Terral Kahklen, Untitled, graphite, micron, and marker on paper, 9" x 12", 2015

Exhibited alongside Jeff Larabee is his good friend and fellow explorer of text aesthetics, Terral Kahklen (TK). TK began coming to the studio late in the year, but immediately began making compelling work. He’s an example of an experience with profound intellectual disability that’s persistently misunderstood and unseen, a person whose way of being demonstrates that being disparate from the neurotypical (far from being a mere impairment in any linear sense), can become a disposition in which making connections between his inner and exterior world (social engagement in a fundamental sense) is a series of creative problems. In effect, his entire engagement with the neurotypical world becomes a creative and aesthetically thoughtful endeavor. Throughout his life, he has elected to be silent and communicate almost exclusively through minimal sign language, allowing himself to be understood on his own terms. For TK, creating elegant, minimalist drawings couldn’t be more natural. His process is exceptionally thoughtful, carefully considering each mark for long periods of time despite consistently choosing to repeat the forms T and K in an exclusively grayscale palette; each of his early works was a singular exploration, but quickly accumulated as a dynamic body of work reflecting a clear perspective.

Melanie Olsen, Twin Lakes, graphite on paper, 10" x 19", 2015

Melanie Olsen, Untitled, graphite on paper, 2015

Melanie Olsen is an eccentric artist who has spent her life surrounded by the majestic, monumental terrains of California and Alaska. In temperament, Melanie is a classic landscape painter, inspired by the beauty and romance of the sublime landscape, and strives to respond to it faithfully in her work. Her drawing process is a collection of brief, intensely focused moments in which she traces long, complicated contour lines, gritting her teeth and drawing almost blindly as her eyes intently follow the jagged mountain edges in her source imagery. In the interest of objectivity, she relies methodically on a range of different grades of graphite to control value in her shading, evaluating tones against a set of graphite swatches. Her works are a highly critical endeavor, not intended to be expressive or personal, but idealistic and true.

In addition to being a fantastic exhibition, NEW VOICES is an achievement of one of the most revolutionary and exciting aspects of progressive art studios: their power to support contemporary, genuine work for the benefit of both local and global art communities. In Juneau, Alaska, the local art community (with a few exceptions) produces and exhibits safe. accessible works - neo-impressionist landscapes typical of rural communities and kitschy illustrative works reflecting a narrow set of themes highly driven by the tastes of tourists, while the beautiful traditional arts of Native Alaskans often remain marginalized. In this cultural landscape, this exhibition is an unprecedented emergence of relevant and compelling contemporary concepts and studio processes.

Karen Wiley, Untitled, graphite and erasure marks on vellum, 12" x 12", 2015