Phoebe Rohrbacher is an artist and former facilitator at The Canvas in Juneau, who is currently living and working in Fairbanks, Alaska. A lifelong Alaskan (born and raised in Juneau), Rohrbacher has a unique perspective on art and disability in rural and remote communities...

Read MoreNEW VOICES

Throughout 2015, Disparate Minds writers Tim Ortiz and Andreana Donahue worked directly with The Canvas, a progressive art studio in Juneau, Alaska as Artists-In-Residence, guest facilitators, and curators of the group exhibition NEW VOICES.

Mike Godkin, Transportation: boat, plane, car, chalk pastel on vellum, 12" x 12", 2015

Jeff Larabee, Untitled, sharpie and marker on clayboard, 16" x 20", 2015

Mirov Menefee, Untitled, ceramic, dimensions variable, 2015

Mirov Menefee, Untitled, colored pencil, graphite, and micron on paper, 18" x 24", 2015

The Canvas is a relatively young studio and when we initially joined them was beginning to transition from a didactic approach to art-making to one of professional development. We were given the opportunity work directly with artists in the studio alongside facilitators to share ideas and knowledge about further developing the emerging creative culture and cultivating an environment conducive to the independent discovery of art-making - guiding artists to invent and maintain studio practices of their own devising. We focused on post hoc guidance through the introduction of criticism in one-on-one discussion and group critique, challenging artists to explore the potential investment of time and care available in each of their processes.

The result of this paradigm shift has been a wealth of inspired new ideas and creative voices. NEW VOICES represents a selection of current work in various media by this studio’s most promising and successful artists, including many that we’ve discussed in essays for Disparate Minds over the past year: the nuanced minimalism of Grace Coenraad, Luis Hernandez’s intuitive yet complex abstractions, the enigmatic text-based drawings of Jeff Larabee, and Susy Martin’s bold, layered symbolism. This exhibition establishes a dialogue between artists and artwork, accentuating similar investigations of visual language and innate tendencies - repetitive processes or subject matter choices, surface manipulation, emblematic mark-making, or heightened attention to detail.

Other highlights from the exhibition include:

Mark Davis, Untitled, colored pencil on paper, 19" x 24", 2015

Mark Davis’ first major work on paper - a complex, pattern-based drawing in colored pencil, created using an intuitive set of rules, built methodically from bottom to top; it’s a spectacle of fluorescent color and rich detail, paradoxically both a simple, flat pattern and organic rendering of form reminiscent of a woven textile.

Terral Kahklen, Untitled, graphite, micron, and marker on paper, 9" x 12", 2015

Exhibited alongside Jeff Larabee is his good friend and fellow explorer of text aesthetics, Terral Kahklen (TK). TK began coming to the studio late in the year, but immediately began making compelling work. He’s an example of an experience with profound intellectual disability that’s persistently misunderstood and unseen, a person whose way of being demonstrates that being disparate from the neurotypical (far from being a mere impairment in any linear sense), can become a disposition in which making connections between his inner and exterior world (social engagement in a fundamental sense) is a series of creative problems. In effect, his entire engagement with the neurotypical world becomes a creative and aesthetically thoughtful endeavor. Throughout his life, he has elected to be silent and communicate almost exclusively through minimal sign language, allowing himself to be understood on his own terms. For TK, creating elegant, minimalist drawings couldn’t be more natural. His process is exceptionally thoughtful, carefully considering each mark for long periods of time despite consistently choosing to repeat the forms T and K in an exclusively grayscale palette; each of his early works was a singular exploration, but quickly accumulated as a dynamic body of work reflecting a clear perspective.

Melanie Olsen, Twin Lakes, graphite on paper, 10" x 19", 2015

Melanie Olsen, Untitled, graphite on paper, 2015

Melanie Olsen is an eccentric artist who has spent her life surrounded by the majestic, monumental terrains of California and Alaska. In temperament, Melanie is a classic landscape painter, inspired by the beauty and romance of the sublime landscape, and strives to respond to it faithfully in her work. Her drawing process is a collection of brief, intensely focused moments in which she traces long, complicated contour lines, gritting her teeth and drawing almost blindly as her eyes intently follow the jagged mountain edges in her source imagery. In the interest of objectivity, she relies methodically on a range of different grades of graphite to control value in her shading, evaluating tones against a set of graphite swatches. Her works are a highly critical endeavor, not intended to be expressive or personal, but idealistic and true.

In addition to being a fantastic exhibition, NEW VOICES is an achievement of one of the most revolutionary and exciting aspects of progressive art studios: their power to support contemporary, genuine work for the benefit of both local and global art communities. In Juneau, Alaska, the local art community (with a few exceptions) produces and exhibits safe. accessible works - neo-impressionist landscapes typical of rural communities and kitschy illustrative works reflecting a narrow set of themes highly driven by the tastes of tourists, while the beautiful traditional arts of Native Alaskans often remain marginalized. In this cultural landscape, this exhibition is an unprecedented emergence of relevant and compelling contemporary concepts and studio processes.

Karen Wiley, Untitled, graphite and erasure marks on vellum, 12" x 12", 2015

Mary Ann James

Heaven, graphite and watercolor on paper, 2015

Train, graphite, micron, and watercolor on paper, 2015

Camping, graphite, micron, and watercolor on paper, 2015

Untitled, graphite and watercolor on paper, 2015

Mary Ann refers to all of her works as her “creations”. Like a story teller, she’s inspired by a combination of personal experiences in her daily life and concepts that she values, such as motherhood and heaven. Consequently, her works have a narrative feel - depictions of people and places that may be part of a story.

Mary Ann’s process, however, is not guided by narrative, but rather by an ambition to create. As a result of this, her subjects aren’t rendered as two-dimensional images, but intended to exist in their own right, in a two-dimensional world. In effect, her imaginative nature inevitably imbues the world she creates with a narrative life, but this distinction in her creative practice is important. Because she's creating rather than depicting, a figure, for example, is drawn in its entirety before clothing is drawn onto it - often a layer of flesh tones is painted before a subsequent layer of paint is added for the color of their clothing. If she includes shoes or gloves for a figure, she draws them around the foot or around the hand, rather than over it. Figures standing in front of a train are placed below the train, rather than in front of it, because both the train and people are created separately. Mary Ann has a highly original way of translating her perception of reference images onto paper, often distorting the scale of objects and editing out details that don’t fit her vision.

In the world she creates, scale is an expressive choice; each form is given whatever space it needs to exist and relate to the world it occupies. Ultimately in her work, she creates people and things to stage a still, timeless moment that’s simple, complete, and good.

Mary Ann James maintains a studio practice at The Canvas, a progressive art studio in Juneau, Alaska.

NEW VOICES

Throughout 2015, Disparate Minds writers Tim Ortiz and Andreana Donahue worked directly with The Canvas, a progressive art studio in Juneau, Alaska as Artists-In-Residence, guest facilitators, and curators of the group exhibition NEW VOICES.

Read MoreGrace Coenraad

Grace Coenraad, Untitled, micron, sharpie, graphite, and india ink on paper, 2015, 16" x 16"

Grace Coenraad, Untitled, micron, sharpie, and india ink on paper, 2015, 22" x 22"

When I first painted a number of canvases grey all over (about eight years ago), I did so because I did not know what to paint, or what there might be to paint: so wretched a start could lead to nothing meaningful. As time went on, however, I observed differences of quality among the grey surfaces – and also that these betrayed nothing of the destructive motivation that lay behind them. The pictures began to teach me. By generalizing a personal dilemma, they resolved it.

Gerhard Richter, From a letter to Edy de Wilde, 23 February 1975

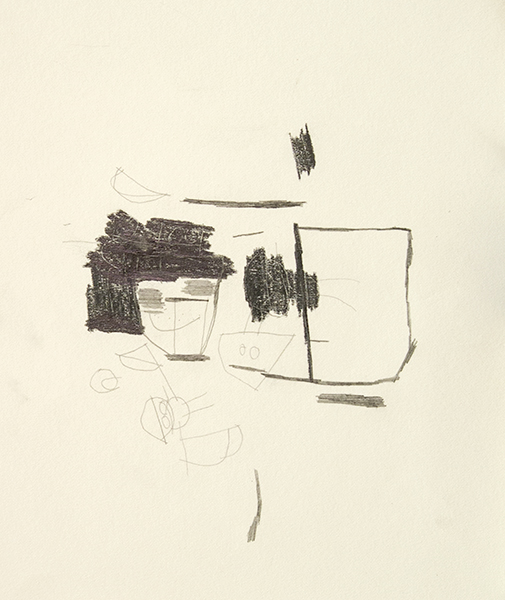

Coenraad’s dark, minimalist works are the product of a measured and slow process, executed with extreme diligence. Using 08 black microns, traditional pen and ink nibs, and occassionally graphite, she densely hatches careful lines, which slowly collect on the surface over many hours of work. This method is a clear path leading to an absolute resolution - the surface being obscured by black. The magic of these pieces (although they’re inextricable from the story of the steadfast execution of this simple method) lies in content that’s fantastically nuanced and complex. The black square is a subtle, jagged field comprised of various sheens and tones - certain patches are tinted by an initial application of bright watercolor (often pink or blue) that has bled through the subsequent, inevitable layer of black. The marks made using microns are incised, and those created with india ink and nib lift the paper slightly away from the surface, resulting in a textured surface reminiscent of Richard Serra’s black oil stick drawings. And much like the reductive, sublime paintings of Richter or Clyfford Still, Coenraad demonstrates that the honest act of mark-making isn’t reduced when it’s stripped of intentions or illusion. Conversely, it only becomes more revealing and mysterious.

After his first museum exhibition of entirely black drawings in 2011, Richard Serra was described by critic Roberta Smith as hermetic, abstract, difficult, and austere, an assessment that he accepted, describing it as “a virtue.” Explaining that art has to be difficult, Serra said that drawing independent of the flamboyance of color interaction, mark-making on its own, in black on white, proves to necessitate invention, thereby providing a “subtext” for how an artist thinks. For him, allover black works were a move to escape that convention of drawing as a “form to ground problem” to create works concerning “interval and space” rather than image.*

Coenraad didn’t stumble upon this principle inadvertently like Richter; for her, it’s a process that reflects a way of being. It is, as Serra articulates, an extension of the thought process and more. To a degree that’s rarely seen for non-performative artists, Coenraad is an artist for whom the boundary between life and art is blurred. Every task is executed with the same resolute sensibility, engaging life with a singular and sophisticated method in pursuit of perfection. Every bite of food is carefully selected and examined before being eaten (ingredients of an undesirable color rejected), every mundane task is afforded great consideration. For years she has worked part-time at a document destruction facility, where no one has been able to compel her to obliterate more than one document at a time. At home, blackening crossword puzzle squares for hours with ballpoint pen or sharpie is part of her daily ritual.

In the studio, Grace is fully immersed in her practice - working with her face close to the surface, she becomes absent from anything exterior of the drawing process. Occasionally she will stop and look around the room for a moment like a deep sea diver rising briefly to the surface, before submerging again. Grace doesn’t discuss her work, not because she can’t, but because there seems to be nothing necessary to say once a piece is finished.

Between her larger, long-term works, Coenraad sometimes creates small graphite sketches, thoughtful experiments that serve as a point of entry into her mysterious thought process. The placement of faces demonstrate the dynamics of orientation in her drawings. The coexistence of elements in combination with turning the paper many times while working isn’t incidental to the process, but essential to it.

Coenraad is a Juneau-based artist who maintains a studio practice at The Canvas in Juneau, Alaska. Her work will be included in an upcoming group exhibition curated by Disparate Minds writers Tim Ortiz and Andreana Donahue at The Canvas' exhibition space in December.

New Work: Susy Martin

Untitled No. 14, charcoal, graphite, and watercolor on paper

Untitled No. 11, charcoal and graphite on paper

Untitled No. 10, charcoal and graphite on paper

In order to fully appreciate this collection of drawings by Susy Martin, it’s helpful to rethink the practice of drawing in terms of its most basic fundamentals - ideas about technique or visual interpretation. The viewer must reimagine drawing in terms of its most essential and universal function - a practice of mark-making that becomes a reflection of a way of being. In every aspect of her life, Susy demonstrates her convictions, adorations, and general understanding of the world through repetition. From her daily routine to interactions with others reiterated verbatim each day, repetition is her foundation; it’s the means by which she navigates the world and the nature of these works.

Rendering the subject of each piece is an important, yet brief step at the beginning of Susy’s process. Usually working from a photo reference, she creates an extremely reduced image that seems to refer to the photo without striving to recreate it, indexing a selection of elements as symbols. In one instance, when working from a photo that she was particularly excited about, she described the photo itself as an object, with a simple, symbolic rectangle repeated many times.

Installation view

Once this initial framework is drawn, the majority of her process is methodical, redrawing over and over in alternating layers of charcoal, graphite, and occasionally watercolor. Although her marks often appear energetic and immediate, the image actually develops at a fairly slow pace (by steadily layering over the original marks of a drawing for hours), growing and changing with each iteration until reaching a point of resolution.

Susy uses photos of friends, found images in books, or in some cases (including a self-portrait) images of Tlingit people posed in regalia.

Installation view of ceramic pieces

“New Work”, a solo exhibition of Susy Martin’s recent drawings, is currently on view until June 29, 2015 in the gallery space of The Canvas, an integrated progressive art studio in Juneau, Alaska. Martin has shown extensively in group exhibitions at The Canvas over the past few years.

New Work: Susy Martin

June 5 - June 29, 2015

The Canvas

223 Seward Street

Juneau, Alaska

Jeff Larabee

Marker on panel, 2015

Marker on Cardboard, 2015

Marker on panel, 2015

Over the course of working in and researching progressive art studios, we’ve encountered many artists who brilliantly incorporate text into their work: the narratives of Oscar Azmitia, rules and records of William Tyler, Daniel Green’s stream of consciousness lists, among many others. Text is usually employed by these artists in creative pursuits because it’s the paramount mode of expression and there’s often no separation between studio practice and daily life. This tendency may be the result of art-making as the most significant form of communication - a disposition which many artists lay claim to, but few truly experience in such a literal and profound way.

We’ve recently had the privilege of getting to know Jeff Larabee, a Juneau-based artist working at The Canvas, an integrated studio in Alaska. These grayscale, marker on panel and cardboard pieces (whose surfaces are wholly devoted to hand-written text), are selections from a recent series. The incredible aspect of Larabee's work is that it’s more fully about written language than the artists mentioned above, despite it being unavailable to him as a tool to communicate.

It’s important to understand that these works aren’t created through an intuitive or automatic process. Larabee always works from a reference - transcribing found newspapers, books, pages of printed text, and often his previous works. Larabee gathers newspapers and carries them with him; he fills in crossword and sudoku puzzles then blacks them out with ballpoint pen, examines articles and classified ads, then blacks them out as well. The process of studying and engaging with newspapers sometimes occupies the majority of his studio time. The romance of his work resides in a study of text akin to the investigation definitive of the work of Tom Sachs, who refers to his process as a form of Sympathetic Magic (the desire to imitate or recreate something whose true nature is unattainable). Sachs explains:

“...when someone like an Aborigine person in New Guinea will make a model of a refrigerator because they saw that missionaries had refrigerators and food was always coming out of them. They made these models of refrigerators, and they would pray to them and hope that food would come out. And they’d even make runways with the hope that airplanes would land on them and docks with the hope that ships would come visit them. In fact anthropologists did come to look at these makeshift docks, and runways, and fridges. So the Aboriginal people, in a way, created their own destiny using art.” (http://www.somamagazine.com/tom-sachs/)

In the same way that Tom Sachs uses intensive study and mimesis to access NASA’s Space Program, Larabee strives to access the written word. Larabee doesn’t experience written language as a literate person does, but experiences, values, and diligently engages with it in his creative practice and daily life. This body of work aspires to the concept of encoding and transmitting information in a purely magical sense, rendering visible to us what is unseen within the text - an aesthetic and conceptual investigation of letters and words, separate from a concrete concept of meaning.

Marker on panel, 2015

From a distance these drawings are alluring - stark, clean, and curious, with the promise of an elaborate message. Up close, they provide no message, but are surprisingly labored and nuanced, revealing ghosts of marks wiped away, shades of grey, and repeated, overlapping letters that build history and depth. In the absence of meaning, the accumulated hand-written forms are strikingly personal. Larabee, uninhibited and confident, ultimately leaves nothing between the viewer and his hand, as if the act of mark-making itself carries the power of the written word.

Although he’s rarely willing to discuss his work, Jeff (an avid Batman fan), has referred to these pieces as “letters to Gotham City.”