Gateway Arts, in Brookline, Massachusetts (just outside of Boston) is one of the largest and, arguably, the oldest progressive art studio in the country, originally founded in 1973 (just prior to the 1974 creation of Creative Growth by Katz in Oakland). Whereas the Katz west coast programs closely resembled the model we consider most progressive for a fine arts program from their inception, Gateway grew into this model over time and continues to do so. Today Gateway is an exicting and important program, home studio to many great arstis including Roger Swike (who was included in “Mapping Fictions” at The Good Luck Gallery), Joe Howe (recently noticed by Matthew Higgs for a potential solo show at White Columns) Yasmine Arshad, Michael Oliveira and many, many, others. The studio currently provides workspace and facilitation to over 100 artists.

Gateway was initially founded in direct response to a deinstitutionalization initiative (then named “Gateway Crafts”) as a weaving and ceramics studio for 10 individuals. Over the past 43 years, the program has grown, evolved, and maintained an effort to stay in touch with progressive ideas. A detailed history of Gateway and their relationship to the emerging progressive art studio movement is detailed in the essay “Outsider Art: the Studio Art Movement and Gateway Arts” by Rae Edelson, who has been the program’s director since 1978.

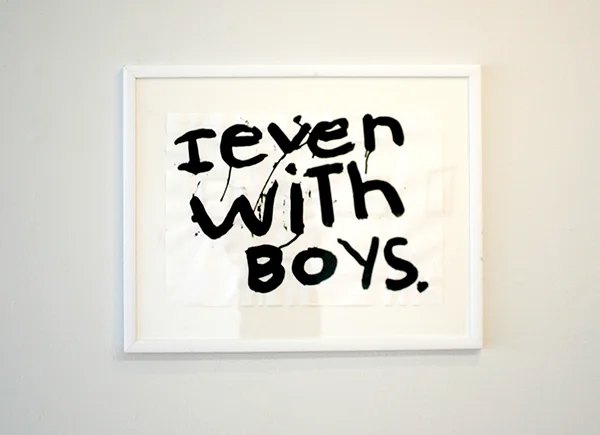

Yasmin Arshad, Untitled, marker on paper, image courtesy Gateway Arts

Gateway’s rich history is evidenced in their exceptionally dynamic approach to every aspect of what they do - the populations they support, the kind of art created, and methods they implement to promote and sell artists’ work. Even as they participate in fine art exhibitions at high level galleries, craft continues to be an important part of their program in a way that may be somewhat subversive to traditional ideas of fine art. More effectively than any other progressive art studio in the country, Gateway sells handmade craft objects in their own retail store, while also supporting the professional fine art careers of several of their artists.

The studio (a space they have been using since 1980) is separated into several sections, each of which is lead by a staff facilitator; artists rotate among the various work spaces from day to day on a regular schedule. This approach is conducive to (or strongly encourages) artists to work in a wide range of media. This isn’t uncommon, many studios have workspaces for various uses, usually based on media (ceramics, printmaking, sculpture, etc.). Gateway has an exceptionally large number of spaces, providing a wider range of ideas, which have come into being over a long period of time and aren’t necessarily defined by media in the typical sense.

Gateway’s main studio includes workspaces for “Pottery”, “Folk art”, “Fabric”, “Paper, “Weaving”, and “Art Making”; in addition to the main studio, “Studio A” provides various creative supports and resources for those with psychiatric disabilities. Each area has a supervisor/facilitator who specializes in its respective media and each artist has a weekly schedule that determines which area they work in daily. A potential problem with this complex structure is that it could distract from an artist’s ability to develop a consistent, independent method of working within any one medium. An artist like Roger Swike, however, demonstrates that Gateway leaves room for artists with a well developed vision to operate independently from this structure when they’re prepared to do so. While Roger may sometimes dabble in other media if he chooses to, he’s free to engage with his own practice of working on paper, that he has developed over the course of his long career with Gateway.

Learning to understand the unlimited potential value of a work of art is an important aspect of being an artist, and an important concept for progressive art studios to endeavor to communicate to their artists. Intuitively, one might imagine that the creation of lower value craft objects in the same space as fine art may undermine the studio’s ability to communicate that concept (and uphold that principle). For many programs, the fine art standard is considered to be directly in conflict with craft for this exact reason. Craft in Gateway’s studio, however, is rooted in a tradition of understanding craft as art on a higher level. Artistic director, Steven De Fronzo explains that during Gateway’s formative years in the 80s, the creative community in the Boston area embraced craft as an alternative to an art world that felt inaccessible, or elitist. In this way, craft was akin to the outsiderism of the time.

The fine art vs craft conundrum has a complicated history in progressive art studios; at its most problematic, craft programs are designed and operated on the assumption that individuals with disabilities aren’t capable of making fine art. In these cases, the studios can become assembly workshops that produce crafty “handmade” objects. In their best form, however, providing resources in a progressive art studio to engage in craft diversifies the opportunities available to artists in a way that is essential. Programs that don’t have an admissions process based on a portfolio review inevitably have many artists who will find craft processes and creativity with functional ends as a more intuitive or appropriate path.

In practice, what's most essential is how the artist chooses one path over the other, and how the standard is maintained - creative projects of any kind are created with as much independence and creative freedom as possible. As the the art world progresses, new facilitators bring new ideas to Gateway - as the use of craft processes becomes more prevalent in contemporary art, the use of craft processes become available in their studio on those terms. Staff facilitators present concepts about art-making in terms of their own expertise; ultimately at any progressive art studio, the onus is on artists to staff as examples, not authorities, with artists making choices about their approach to art independently. The critical element is that this relationship is understood by the staff, and independence or divergence from the structure is encouraged when it begins to emerge.