Alan Constable has been creating and exhibiting work in various media for the past thirty years, including painting and drawing, but it is the extensive body of ceramic works he has formed over the past decade that has increasingly garnered attention and acclaim...

Read MoreDisabled Artists Show Us a Way Forward Against a Trump Adminstration

The rise of Donald Trump over the past year has been for us, like many, a growing dread - not wanting to believe that America would really elect an unfit candidate, while watching both political parties and the news media self-destruct in the face of a changing world....

Read MoreSusan Te Kahurangi King: Drawings 1975 - 1989

Susan Te Kahurangi King’s current exhibition marks her second, highly anticipated solo show at Andrew Edlin, following the critically acclaimed debut of the New Zealand-based artist with the space in 2014, Drawings from Many Worlds. Known for her vibrant and frenetic biomorphic abstractions, Drawings 1975 - 1989 curated by Chris Byrne and Robert Heald features a lesser known series from her prolific and consistently impressive practice...

Read MoreMapping Fictions at The Good Luck Gallery

We recently had the honor of guest curating an exhibition at The Good Luck Gallery, an important, new space in Los Angeles. Founded and directed by former Artillery publisher Paige Wery, The Good Luck Gallery is the only space in LA dedicated to showing the work of self-taught artists. Wery fosters the burgeoning careers of artists such as Helen Rae and Deveron Richard, who maintain studio practices in progressive art studios, as well as artists like Willard Hill, who fall into the Outsider, Visionary, or Vernacular categories. Mapping Fictions, curated by Andreana Donahue and Tim Ortiz, opened on July 9th and will be on view through August 27th.

Read MoreMapping Fictions: Daniel Green

Daniel Green, Fifteen People, 2009, Mixed media on wood, 14.25 x 22.5 x 1.75 inches

Daniel Green, Little Mac vs Soda Poponski, 2015, mixed media on wood, 11.5 x 15 inches

Daniel Green, The Sun, 2015, mixed media on wood, 6 x 16.5 x 1 inch

Daniel Green, Business Delivery, 2011, Mixed media on wood, 13 x 29 x 1 inches

Daniel Green's process is slow and intimate; quietly hunched over his works in the bustling studio, he draws and writes at a measured pace. These detailed works are an uninhibited visual index of Green’s hand; when read carefully, they become jarring and curious, slowly leading the viewer to meaning amid the initial incoherence. Green’s text is poetic and complex - language and thought translated densely from memory in ink, sharpie, and colored pencil on robust panels of wood. Figures and their embellishments are drawn without a hierarchy in terms of space occupied on the surface; they are at times elaborate and at other times profoundly simple. The iconic figures’ facial expressions (Jesus, Abraham Lincoln, Tina Turner, video game characters, etc.) are generally flat with proportions stretching and distorting subject to Green’s intention.

Ultimately, these drawings compel the viewer to internalize and decipher Green’s ongoing, non-linear narrative. His drawings call to mind Deb Sokolow’s humorous, text-driven work, but are less diagrammatic and concerned with the viewer. In an interview with Bad at Sports’ Richard Holland, Sokolow elaborates on her process:

I’ve been reading Thomas Pynchon and Joseph Heller lately and thinking about how in their narratives, certain characters and organizations and locations are continuously mentioned in at least the full first half of the book (in Pynchon’s case, it’s hundreds of pages) without there being a full understanding or context given to these elements until much later in the story. And by that later point, everything seems to fall into place and with a feeling of epic-ness. It’s like that television drama everyone you know has watched, and they tell you snippets about it but you don’t really understand what it is they’re talking about, but by the time you finally watch it, everything about it feels familiar but also epic. (Bad At Sports)

Much like Sokolow, Green engages in making work that begins with the rigorous practice of archiving information culled from his surroundings and interests, which then develops into intriguing, fictitious digressions. Dates and times, tv schedules, athletes, historical figures, and various pop culture references flow through networks of association - “KURT RUSSEL GRAHAM RUSSEL RUSSEL CROWE RUSSEL HITCHCOCK AIR SUPPLY ALL OUT OF LOVE…” Although the listing within his work sometimes gives the impression of being intuitive streams of consciousness, most of it proves to be very structured and complex within Green’s system. Rather than expression or even communication, the priority seems to be the collection of information or organization of ideas; the physical encoding of incorporeal information as marks on a surface is a method for making it tangible, possessable, and manageable.

Daniel Green, Pure Russia, 2011, Mixed media on wood, 9 x 23 x 3.5 inches

Pure Russia (detail)

From the perspective that Green invents, there’s an endless number of time sequences that haven’t been considered before. A grid of days and times (as in Pure Russia) imagines time passing in increments of one day and several minutes, then returns to the beginning of the series, stepping forward one hour, and proceeding again just as before. It could be cryptic if you choose to imagine these times having a relationship to one another, or it could instead be an original rhythm whose tempo spans days, so that it can only be understood conceptually as an ordered structure mapped through time - the significance of the pattern superseding that of specific moments.

By blurring the distinction between the articulation of ideas through text and the development of mark-making, Green’s highly original objects become unexpectedly minimal and material, yet simultaneously personal and expressive.

Daniel Green’s work will be included in Mapping Fictions, an upcoming group exhibition opening July 9th at The Good Luck Gallery in LA, curated by Disparate Minds writers Andreana Donahue and Tim Ortiz. Green has exhibited previously in Days of Our Lives at Creativity Explored (2015), Create, a traveling exhibition curated by Lawrence Rinder and Matthew Higgs that originated at University of California Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (2013), Exhibition #4 at The Museum of Everything in London (2011), This Will Never Work at Southern Exposure in San Francisco, and Faces at Jack Fischer Gallery in San Francisco.

Knicoma Frederick

Knicoma Frederick, Untitled (Candle Army Eyes) from the Series 80 Bit, 2006, Acrylic on canvas, 24” x 18”

Knicoma Frederick, Glory News Article from the Series Information 1600, 2012, marker and pen on paper, 8 ½” x 11”

Knicoma Frederick, Untitled (Elaborately Painted Pedicure) from the Series 80 Bit, 2008, colored pencil on paper, 8 ½” x 11”

Knicoma Frederick, from the series Die Evil 82, 2013

Knicoma Frederick, Unitled (Couple Painting/Interior) from the Series 80 Bit, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 24 inches

“The painting is not on a surface, but on a plane which is imagined. It moves in a mind. It is not there physically at all. It is an illusion, a piece of magic, so what you see is not what you see … I think that the idea of the pleasure of the eye is not merely limited, it isn’t even possible. Everything means something. Anything in love or in art, any mark you make has meaning and the only question is ‘what kind of meaning?” - Philip Guston

Prolific visionary Knicoma “Intent” Frederick has lived the intensely dedicated life of an artist for whom painting is more than painting - it’s a way to access something deeper than merely tangible or social ends. Frederick’s work engages the practice of image design and creation with a mystical or prophetic intent, relying on and striving to access and utilize the magic inherent in the process of painting.

Sometimes remarkably akin to the work of William Scott, Frederick’s work possesses an abundance of idealism, realized as utopian visions of the future - proclamations from Glory News, superhero first responders defeating armies of demons, or a “love and justice” rocket ship flying overhead. Where Scott has a steadfast tone of praise and celebration, however, Frederick’s narrative works also include darker, stranger, sometimes ominous themes that afford them a sense of gravity, conflict, and romance.

Knicoma Frederick, Untitled (Couple Painting/Beach Scene) from the Series 80 Bit, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 36" x 24"

Works such as Untitled (Couple Painting/Beach Scene) live in a space characterized by a more cryptic sort of mysticism, in which painting becomes not only the method that Frederick employs, but also becomes incorporated into the content of the image - overtly, when paintings are included in the image, and less explicitly when “painting” as an archetype is present in the work via the presence of painting tropes (such as a dramatic seascape or elements of traditional still life). These tendencies also present themselves in the work of Los Angeles based painter John Seal.

In response to our inquiry about Frederick and the concept of paintings of paintings Seal remarked:

"The magic, really, is in the disconnect/misconnect. It is in the way the subject and its material delivery interface/intermesh with the viewer's life experiences--it is the surprise of finding anything in common, the surprise of seeing one's self, altered and new, reflected in the painting which in turn becomes new in the viewer's eyes. The magic is in this dual rebirth of viewer (subject) and painting (object). The magic is the painting's ability to make this dual rebirth visible. Painting paintings of paintings is, to me, a way to lead people into the mechanics of image, and to invite the viewer to examine their own relationship to looking: if a picture can be captured by a picture via the means (language) of painting, what can it do to the rest of the world?"

Knicoma Frederick harnesses these mechanics to not only compel the viewer to reflect on the capacity of painting, but to also assert the presence of his message in the world he envisions. The "dual rebirth" that painting facilitates is, for Frederick, a pathway into this realm that his work manifests, and painting is explicitly the magic by which this manifestation takes place.

In the course of discussing his WPIZ series of artist books, and a fictional video game called ArtFighter (which exists within WPIZ) Frederick articulates his manipulation of this mystical function of painting:

"People have heard of games like ‘Street Fighter’ and ‘Mortal Combat’ and ‘Tekken’ for PlayStation and XBox and all of those different types of game systems…But ‘Art Fighter…is fighting with artwork. You’re taking artwork and you’re fighting the situation with it. You’re taking a picture that represents what you want to have happen, done by the storyline in each book. You’re taking a picture, and you’re destroying the negative with it…I have an obligation to make the WPIZ so that the books are used for overcoming the evil that’s in the people’s way." (source)

Shortly before the establishment of the Creative Vision Factory (where Frederick maintains his studio practice), Director Michael Kalmbach encountered Frederick attempting to get permission at a drop-in mental health center to use the copy machine (unsuccessfully), presumably for the distribution of a handwritten series of newspapers (in the neighborhood of six hundred pages). Kalmbach cites this event as instrumental in the development of CVF (informing its goals, design, and function), not only due to the magnitude of this endeavor, demonstrating the need for and potential value of a studio of this kind, but also that the content of these newspapers provided important insight about both Frederick's personal experience and the mental health system in general.

Frederick’s works are conceptualized as series of books for which each work represents a specific page. Over the four years that he has been with CVF, he has published more than 25 artist books, each comprised of 125 - 150 works; prior to the publishing a book, the works can not be sold individually. Frederick has an extremely productive creative practice; Kalmbach estimates that he creates roughly 1000 works per year.

Knicoma Frederick is originally from Brooklyn, New York, but is currently based in Wilmington, Delaware. Recent exhibitions include All Different Colors and Outsiderism at Fleisher/Ollman in Philadelphia and previously at numerous venues in Wilmington, Delaware. He has work in the permanent collection of the Delaware Art Museum and is the recipient of an Emerging Individual Artist Fellowship from the Delaware Division of the Arts.

Full Life

Full Life in Portland, Oregon (founded by Rachel Bloom in 2004) is a unique and dynamic program whose methods are informed by client choice with more depth and ambition than most service providers of any kind that we have encountered. Full Life is funded as a day program and receives no private donations; they’re technically for-profit, although profits tend to go only into the development of more programming.

Full Life began as an open art studio and is still centered around this format, but now offers a wide range of daily recreational and vocational programs including work in their own “Happy Cup” Coffee Shop, janitorial assignments, employment in a greenhouse and chicken farm, and a wide range of creative arts classes and projects, among many other options. The Full Life staff, a team of 20+ creative people, are all given agency to develop and introduce new programming and opportunities to offer. The schedule is incredibly diverse (and in constant flux), initiating and retiring activities organically. Because staff working directly with individuals are also involved in developing the programming, what is offered (and when) can be constantly tracked based on demand and interest. The art studio portion of the facility is always open for clients to come to between projects or when they lose interest in a project they’re signed up for.

The program serves around 160 individuals who attend five days per week, split fairly evenly into two 5 hour shifts (morning and afternoon) with a one hour overlap. Their most impressive achievement is that they offer this wide range of opportunity to their large community of clients with incredible flexibility. Each person chooses his or her daily activities at Full Life (not only with a team in an annual or quarterly planning meeting, but independently every day).

This scheduling board hangs in the reception area; the programming offered is updated daily and each person comes to the reception desk in the morning to plan their day - their name is written under the activities that they wish to attend and then staff use this schedule to understand their own schedules for the day. Opportunities on the board include everything from paid employment in the community to foosball tournaments and karaoke.

Steve the Program Director states “everyone has the right to work, if they want to”, elaborating that an individual granted a subsidy to live on due to unique social, physical, and intellectual struggles should be offered opportunities, but not forced to be employed if they’re satisfied with an unemployed life. Full Life is committed to offering individuals the opportunity to excel in whatever manner suits them, rather than attempting to encourage them to be excellent in some consensus paradigm of what it means to be productive or employed. An individual decides whether or not to work each morning and everybody is encouraged to do well in whatever they choose to do. Ultimately, in spite of this unconventional approach to considering employment, Full Life offers about as much traditional employment as any program of its size serving a comparable population.

The question of whether art is understood as recreation or career isn’t answered by Full Life, but is instead determined by the ambition of each artist. Full Life sells some artwork, but customers are almost exclusively Full Life staff. Artists are permitted to take works home and to make artwork as gifts for friends.

An important lesson to take away from Full Life is the depth of meaning that some of the projects achieve as a result of the cultivation of a community driven by individual choice. Although they don’t tend to produce cohesive bodies of work for exhibition, they do complete works that have deeply understood meaning within the context of the Full Life community. A large, collaborative, and ever-changing window display is a voice of the community, that is for many a more intuitive way to speak to the outside than a delicately presented gallery exhibition.

These championship belts also play an important role in foosball tournaments that staff person Rob Gray describes as “a very big deal around here.” Works like these can be viewed as art objects, somewhat like aboriginal masks in a museum case, where the intensity and adoration with which they are crafted could be well understood and respected. But within the realm of Full Life, they have a greater and clearer meaning than they could really achieve elsewhere. Because work is allowed to be entirely personal, many works are kept by the artists or created for a particular person; one could likely collect from the staff offices a very endearing collection of works.

This philosophy grants the freedom for the facility to become an art studio in a more natural sense. It’s a place that not only creates projects, but also explores ideas. Staff are empowered to develop programming at any time and are therefore able to devise projects that respond to the concerns and interests of the artists in the moment. Some projects are intended to develop skills and introduce concepts that empower, others resemble something more like a collaboration between staff and artist (truly between artist and artist). The result is a committed team of staff, an empowered and satisfied group of clients, and an exceptionally strong culture of mutual respect. There are truly beautiful examples of artists enabled to achieve excellence, such as the poetic works of Marvin Asino, who is supported by Full life to participate in readings and access local creative writing communities. The culture cultivated by Full Life’s deeply person-directed methodology is described by the various creative projects they produce collaboratively, whose sole function seems to be expression of their community, such as this video, “when you least expect it”

Marvin Asino

From the Disparate Minds collection: “For all of my friends and one basketball player” is a zine containing 21 poems interpreted from the text works of Marvin Viloria Ariza Asino. It’s sensibility can be described using Marvin’s own words “rhythm; kind, beautiful, friendly.” Asino writes in a matter-of-fact manner (siding in a space where humor and simple, profound truths meet), so the force of its beauty comes entirely by surprise with a wonderful sense of mystery.

This anthology was given in the course of a conversation with one of Marvin’s many friends, Robert Grey, at Full Life, in Portland Oregon last year. An updated overview of Full Life, a very different kind of program, will be posted soon.

Billy White

My Body, mixed media on canvas, 18" x 24", 2015

Jed Clampett, glazed ceramic, 10" x 7" x 4"

Untitled, acrylic, 18" x 24", 2015

Untitled, graphite on paper, 12" x 17"

Untitled, mixed media on canvas, 24" x 18"

The process of evaluating any artwork includes some interpretation of how it functions - mechanisms such as the way gestural brushstrokes communicate movement by indexing the physical action of their application, or the way that arrangements of representational imagery can imply relationships between elements that generate narrative.

The mechanism by which Billy White’s paintings elicit emotion is sharply specific, yet escapes analysis, remaining a wonderful mystery. A loose, fearless application of paint renders forms with a striking physicality and sense of humor. There’s an uncanny affinity with the work of figurative painters Todd Bienvenu and Katherine Bradford (who both have an aesthetic undoubtedly informed by the work of self-taught artists). The impact of White’s work cuts through a vivid alternate world that operates on White’s terms - a highly original set of priorities, passing over image and rendering to achieve an expression of mood and vitality, as though excavating the underlying stories that were already present; impatient mark-making and barely legible imagery find time and space for redolent storytelling and detail. While he typically focuses on painting and drawing, White occasionally creates small ceramic sculptures that are rich in character and evocative of Allison Schulnik’s warped clay figures - slumped postures, elongated, rubbery appendages, intermingling glazes, and sunken, cartoonish expressions.

White’s work is largely influenced by his avid interest in pop culture, often depicting actual and imagined events in the lives of various celebrities or fictional characters, from Dr Dre to Hulk Hogan to Superman. NIAD provides some insight into White’s process: “He might start off painting Bill Cosby, but quickly change his mind by lunch. When that happens, he simply works right on top and doesn’t erase what came before. The new work becomes an extension of the old. By the end of the day this could happen several times and what’s often left is a latticework of figures and stories with interchangeable meanings.”

Billy White (b. 1962) has exhibited previously in Rollergate at the Seattle Art Fair, Telling It Slant organized by Courtney Eldridge at the Richmond Art Center, Undercover Geniuses organized by Jan Moore at the Petaluma Art Center, ArtPad San Francisco at the Phoenix Hotel, and extensively at NIAD Art Center, where he has maintained a studio practice since 1994. He has an upcoming solo exhibition at San Francisco’s Jack Fischer Gallery later this year.

Julian Martin

Untitled (motorbike), pastel on paper, 15" x 11", 2014

Untitled (White on Cream), pastel on paper, 15" x 11 1/4", 2010

Untitled (Orange Shape and Khaki), pastel on paper, 15" x 11 1/4", 2010

Untitled (parrot), pastel on paper, 15" x 11", 2014

Like other progressive art studio artists at the Outsider Art Fair, Julian Martin works from found imagery culled from magazines (often art publications). Whereas Helen Rae pushes found imagery to greater levels of complexity and reality, and Marlon Mullen and Andrew Hostick retell images in their own vocabularies, Martin pares the image down to a series of perfectly resolved moments in which a series of forms (each powerful and resolved in their own right), is described with an abundance of velvety pastel marks applied deliberately and seamlessly with a deft touch. Martin achieves a ubiquitous softness - soft colors, shapes, surfaces, and materials, yet always precise and controlled in application, saturating the surface while maintaining the boundaries of each form with conviction.

Initially, Martin’s work seems aesthetically akin to the work of many young artists currently revisiting concepts of early abstraction with suggestions of the figure, such as Brooklyn-based painters Austin Eddy and Tatiana Berg. However, where these artists revisit and re-imagine the ideas of artists like Picasso and Dubuffet, who were themselves appropriating the aesthetics of outsiders, Martin is the real thing. Not in that he is a “real outsider” (at this point Martin is quite well established professionally, certainly as much an insider as any artist living and working in Melbourne), but rather that his works, in sum, lack any tone of irony or nostalgia; the strength of resolution that each of Julian Martin’s drawings finds is achieved through a minimalist’s sensibility, preoccupied with the absolute rather than a historical context, more comparable to Malevich, Gottlieb, or Mondrian than Cubism or Art Brut.

The proposition underlying Martin's work seems to be that a found image may, inevitably or inherently, possess a more perfect resolution that can be exposed through a measured and thoughtful process of reduction. Unlike Mondrian, the absolute is not found in total abandonment of the original, but in the poetic and specific distillation of the identity and expression of the image.

Martin has attended Arts Project Australia in Melbourne since 1988 and has exhibited extensively at various venues in Melbourne since 1990. He has also shown previously at Fleisher/Ollman (Philadelphia), several Outsider Art Fairs (NYC), Museum of Everything (London), MADMusée (Belgium), Phyllis Kind Gallery (NYC), Jack Fischer Gallery (San Francisco), among others. Martin is represented by Fleisher/Ollman and Arts Project Australia.

The Effortless Humor of Michael Pellew

Michael Pellew, Untitled, 2016, Mixed Media on Paper, 11"x17"

Michael Pellew, Michael and Latoya Texting on the Beach, 2015, Acrylic on Canvas, 12"x9"

Michael Pellew, British Platter, 2015, Mixed Media on Paper, 14"x17"

One of the fantastic surprises at the Outsider Art Fair this year was our experience with the work of Michael Pellew. Pellew’s work is unassuming, and in the context of the fair particularly blends in - a style defined by repetition, drawing within a simple system, and the use of unconventional materials (markers). We were more familiar with his series of small original drawings marketed as greeting cards, which typically feature a grouping of four or five figures (available at Opening Ceremony in Manhattan and LA). In a larger scale, the voice only available in snippets in smaller works unfolds to become an astonishing comedic performance.

The repetition and economy of visual language in his work is necessary to the humor - each figure articulated in an identical manner, with just a few distinctive features describing its specific identity. The supreme ease with which each character enters the scene via this agile visual vernacular accounts for the works’ pace and timing. There's an exciting cleverness in the way the simple archetype of the figure takes on the identity of countless celebrities, analogous to a skilled impressionist mimicking pop culture icons in rapid succession. Pellew seems to be compiling an ongoing, shifting catalog of celebrities; those with apparent relationships or categorizations are sporadically interrupted with unexpected pairings (Princess Diana and Lemmy Kilmister) or fictional personas (Lauryn Hill M.D. from Long Island College Hospital, The Phanton Lord). Viewers with an extensive knowledge of pop culture are highly rewarded by the ability to recognize the abundance and subtlety of his references.

Michael Pellew, Untitled, 2015, Mixed Media on Paper, 22"x30"

Humor is an important element in many works that don't necessarily make us laugh, but truly funny art like Pellew’s (beyond the occasional clever moment or inside joke), is very uncommon. Crystallizing the elusive and ephemeral quality of comedy into a permanent art object is extremely difficult to achieve. Usually the most overtly funny approach is to employ an explicit punchline that rests on an impressive technical or procedural spectacle; artists that exemplify this approach are those like Wayne White or Eric Yahnker.

Eric Yahnker, Beegeesus, 2005, 13 x 10 x 10 in.

"Bible whited-out except that which sequentially spells Bee Gees" image via www.ericyahnker.com

Pellew’s humor, however, is more nuanced, so in the absence of a punchline, his approach relies on absolute fluency rather than overt technical prowess. The quintessential example of this brand of humor is Raymond Pettibon; works that appear effortless afford the artist a more casual voice, equipped to cultivate a more dynamic interaction between the work and viewer. When it's less obvious that there's a joke present, the viewer tunes into a more acute examination of tone and timing in search of the artist's intention.

Raymond Pettibon, image via www.raypettibon.com

Whereas Pettibon uses this approach to insert sardonic or satirical moments of levity into his generally grim oeuvre, Pellew instead engages this sort of humor with a lighter and even silly sensibility; he creates an abundantly bright and positive space that is captivating. The conceptual foundation of his work becomes about treading the line between earnestly identifying as an artist, or slyly engaging in play-acting the role of an artist. Walton Ford has described using play-acting (as a scientific illustrator) in a similar way as an entry point into comedy. In Pellew’s case, the performance is broader, and in its execution more engrossing - guiding you through his alternate world, you're always uncertain if he’s serious, even as he crosses well over into the realm of absurdity.

Michael Pellew, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 2014, Acrylic on Canvas, 14"x11"

In the affable universe he realizes, there’s virtuosity in the way moments of comedic surprise cut sharply through. The lingering experience of these pieces isn’t static, but a dreamlike memory of an event unfolding; line-ups of celebrities…everyone had a pepsi…they were all hanging out around a limousine eating McDonalds…and then Marilyn Manson is offering his famous burger and fries. It’s an alternate reality composed of familiar characters and Pellew is leading us along, introducing each of them, all in his voice - but really it's the viewer’s voice. You are left walking away amused, incredibly satisfied, but not entirely sure what has just happened.

Pellew has been working at LAND Gallery’s studio for over ten years and participated in numerous exhibitions in New York, including group shows at Christian Berst Art Brut and the MOMA. His work has been acquired by many reputable collectors, including Spike Lee, Sufjan Stevens, Citi Bank, JCrew and PAPER Magazine.

Michael Pellew, Making a Band (detail)

Masters and Emerging Artists at the Outsider Art Fair

Art Project Australia’s Julian Martin at Fleisher/Ollman

At the 24th annual Outsider Art Fair in New York, it was clear that there has been a profound shift. Superficially, the aesthetics are far from the folk art antique shop feel of the past, having assimilated to a presentation more typical of the mainstream - a change generally attributed to one of field’s most successful champions and current fair organizer, Andrew Edlin. On a deeper level, the definition of “outsider” is flexed to a degree that's able to contain a broad spectrum of idiosyncratic works - from the visionary scarecrows of the late Memphis-based artist Hawkins Bolden, to Marlon Mullen’s lush abstractions, to an installation of 3D printed sculptures designed by 65 unconnected collaborators (presented as the work of a manufacturing company, Babel curated by Leah Gordon). Abandoning category without losing identity, the context of this forum has evolved rapidly over the past few years.

In a review of the fair for Design Observer, John Foster recalls that at the inception of the genre, early outsider art dealer Sidney Janis introduced the concept that “serious art could be made by everyday people”, a notion that's difficult to sympathize with today (if artists aren't “everyday people” then what are they?). This train of thought still seems to have some novelty for some 74 years later, as illustrated by Barbara Hoffman’s odd New York Post headline “The artists at this amazing fair are prisoners, janitors, and mental patients”. Ultimately, Edlin has allowed the fair to begin to merge seamlessly with the mainstream by expanding to include a flexible set of principles rather than depending on this particular kind of romantic narrative structure. It’s no longer necessary that the artists work in isolation or live obscure, misunderstood lives.

Rather, it’s a space for excellent creative endeavors that are genuine and created for their own sake, or for a context not ordinarily included in the art world. The most essential principle underlying this movement is that the institution of the market isn’t what engenders great work. In a climate where Laura Poitras (a filmmaker and journalist with no prior fine art experience) has a significant exhibition opening today at the Whitney, the particular terms and intent with which the OAF brings divergent, highly original perspectives to the art world maintains a distinct and important purpose.

The beauty of this more elastic definition is its efficacy both presently and retroactively, indicating that this isn’t so much a shift in paradigm as a greater understanding of why these works have been so compelling all along.

Hawkins Bolden at Shrine

As usual, titans of the self-taught canon were featured extensively throughout the fair: Henry Darger, Joseph Yoakum, Adolf Wolfli, Jesse Howard, Bill Traylor, Thornton Dial, Minnie Evans, Martin Ramirez, Gayleen Aiken, Frank Jones, Royal Robertson, and James Castle, etc. These masters (the ones who have inspired so many to work in this field) continue to be represented by fantastic works, not due to a traditional romantic narrative, but because of genuine, sophisticated, and highly original visions, as evidenced by their conceptual harmony with work by contemporary “outsiders”.

The fair's strongest and most relevant exhibitions, however, were contemporary works by artists who maintain studio practices at progressive art studios - a dynamic collection of installations that were, in sum, a tour de force eliminating any question about their importance to this emerging sub-market, and potential to sustain, develop, and gain momentum.

Marlon Mullen at JTT/Adams and Ollman

Marlon Mullen, NEWS (P0329), acrylic on canvas, 24" x 36"

The fair’s most important moment, and starkest example of the flexed "outsider" categorization, was the joint exhibition of NIAD’s Marlon Mullen by New York’s JTT Gallery and Portland’s Adams and Ollman - a solo exhibition of reductive acrylic paintings, with content explicitly referencing the contemporary mainstream. The narrative justification for its inclusion would be the assumption that these abstractions are defined by an unusual way of thinking and seeing, as opposed to a neurotypical artist’s contrived deconstruction of found imagery. Whether Mullen is engaging in abstraction in the traditional sense, creating representationally from his own perspective, or whether there is no meaningful difference between representation and abstraction in his experience is impossible to determine. Ultimately, their genesis becomes irrelevant because the elusive power of the imagery is an amalgamation of the inherently expressive nature of the work's formal elements, which isn’t dependent on a mutually understood way of seeing. The real triumph and importance of Mullen’s work lies in the revelation that their mysterious conceptual origin only causes their success to be more fascinating, and that they’re pushed to a degree of technical sophistication that’s unmistakably impactful. His paintings are paradoxically thoughtful and casual, as awkward as they are bold, as messy as they are delicate. These pieces embody a deeply genuine and intuitive quality that coexists with a strength defined by specificity and fine tuning.

Helen Rae at The Good Luck Gallery

Helen Rae, July 1, 2015, colored pencil and graphite on paper, 24" x 18"

The fair’s most generous moment was The Good Luck Gallery’s installation of stunning Helen Rae drawings - surfaces saturated with vigorous mark-making culminate in robust, stylized worlds rendered in graphite and colored pencil. Rae’s counter-intuitive re-imagining of the boundaries between abstraction and representation are thrillingly confounding. Strong graphic or patterned passages have an inexplicable sense of depth and form, which transition into fields scattered with spare details, achieving an almost photographic quality - all of which emerges from a surface that (when examined closely) possesses a roughly inscribed physicality. The continuous stream of excellent new drawings replacing sold work served as a testament to the promise of this prolific septuagenarian as an emerging phenomenon to watch.

Andrew Hostick at Morgan Lehman

Photos do little to capture the true nature of Andrew Hostick's drawings at Morgan Lehman Gallery. Not evident above is the experience of approaching this simple red, blue, and brown figure eight to discover that it’s surrounded by an opaque, shimmering field of marks in white colored pencil, worked hard into the mat board surface. The mystery of choosing to color a white surface white, is in its own way explained and not compounded by its eventual effect: fantastic moments of wonder in a distinct and familiar space. The curious effect of this subtlety achieved in such a laborious manner lays a foundation for the elusive mood that runs throughout all of Hostick’s works. He seems to search for, and with great success, achieve abstractions that aren’t just poignant in a general sense, but evoke a beautifully bleak, arid quality that seems to romantically belong to Ohio.

Andrew Hostick, Leon Polk Smith: A Constellation with Works on Paper, graphite/colored pencil on mat board,

Kenya Hanley, Family Matters, 2015, Mixed Media on Paper, 17" x 14", image courtesy Land Gallery

Other highlights included the velvety pastel abstractions of Art Project Australia’s Julian Martin at Philadelphia’s Fleisher/Ollman, humorous, pop-culture driven drawings by Kenya Hanley and Michael Pellew at LAND Gallery, Harald Stoffers at Cavin Morris Gallery, Joe Minter and Lonnie Holley at James Fuentes, Evelyn Reyes, Daniel Green, and Camille Halvoet at Creativity Explored, Terri Bowden, Susan Janow, and William Scott at Creative Growth, Walter Mika and Victor Critescu at Pure Vision, and an impressive quantity of work by artists at Japanese studios. Although only 4 progressive art studios exhibited independently at this year’s fair, their respective artists were prominently featured in a quarter of the exhibitions, including those of the most prominent dealers.

Henry Darger and Judith Scott at Andrew Edlin

Susan Janow, Untitled, colored pencil and micron on paper

Harald Stoffers, Brief 164, March 10th, 2012, ink on paper, 39.25" x 27.5", image courtesy Cavin Morris Gallery

Lonnie Holley at James Fuentes, NY

One of the most important insights from this year's Outsider Art Fair is that the progressive art studio can no longer strive to position itself as a neutral, invisible player between self-taught artists and an outsider art gallery. Undeniably, progressive art studios are poised to be a truly important movement, but, reflecting on this changing landscape it’s important that they critically evaluate their role in presenting work to the market. Despite their prevalence at the fair, gallerists had no reservations about expressing that they’ve been forced to stop representing artists they believe in due to studios' failures, ranging from unethical behavior (such as gifting works to program board members) to providing intrusive facilitation to simply being disorganized. The process of translation from outsider to the mainstream fine art market is delicate, and is something outsider art dealers are just now learning to do effectively; they’ve been an asset to studios because of their willingness to represent unique artists without ties to the broader art community. As the distinction continues to break down between outsider and insider, however, studios can only continue to be relevant if they’re able to proactively take on the responsibilities of translation and promotion typically provided by gallerists (including handling and documenting artwork properly).

The future of this process is pioneered right now by career paths that resemble the ones profiled above: NIAD, JTT, Adams and Ollman, and Marlon Mullen; Visionaries + Voices, Andrew Hostick, and Morgan Lehman; First Street, Helen Rae, and Good Luck Gallery; and Creative Growth, William Scott, and White Columns. Progressive art studios must believe in and champion each of their great artists with respect for their individual vision, with a focus on developing careers that extend beyond their program of origin.

Mark Hogencamp, Untitled (IMG_2616), Digital C-print, 27" x 36", 2014

In the traditional narrative of outsider art, the career of an artist such as Mark Hogencamp would have ended with the initial discovery of Marwencol. Ideally in the past, he would have been deceased before the work was found and his fixed oeuvre would be intrinsically associated with the story of a strange man working in isolation and obscurity (much like Darger and Ramirez). Mark Hogancamp, however, is no longer obscure or working in isolation. His new work at this year's fair, scenes created using full-sized mannequins, are a clear and exciting new development in his creative process. Hogancamp’s work is not at all diminished by the open involvement of his facilitator and gallery director Eddie Mullins, who we spoke with at One Mile Gallery’s booth. In our conversation with Mullins, his relationship with Hogencamp was remarkably familiar. Marwencol is a project absolutely devised and driven by Hogencamp, but Mullins has no inhibitions about explaining that the use of mannequins began after he provided some for Mark. Mullins plays an instrumental role in how Hogencamp’s vision is ultimately seen as art, but his assistance isn’t mistaken for collaboration (much like the relationships sound engineers and producers have with musicians). In this way, the transparency of this relationship sets an important example for studios to follow.

Recognizing the true nature of the facilitated creative process, including that provided by artist staff in the studio, must be fully open to criticism in order to progress; it’s simply too personal, dynamic, and delicate to be left out of the discussion. The next wave of great artists will come out of progressive art studios that are not only assisting artists to initiate a creative practice, but also provide innovative and ambitious new facilitation methods to further develop dynamic bodies of work.

Discussing Biography

Judith Scott in the studio, image via Creative Growth

Over the past several years, as work created by artists working in progressive art studios (as well as those historically categorized as outsider or visionary) has entered the mainstream, questions have emerged about how to appreciate and discuss these artists. What does it mean to contextualize this work as fine art? What really defines this categorization? What role should the artist's disability or dispositional narrative play in understanding the work? Responding to these questions often seems to result in skirting or avoiding the consideration of an artist's biography.

Fear of overstating biography is rooted in a fair desire to understand these artists on a level playing field with their contemporaries, trying to avoid both an especially generous consideration and a disparaging framing of “other” (necessarily lesser) - seemingly opposite ideas that are in effect the same, a phenomenon which we refer to as the “sympathetic eye”. This dismissive perspective suggests that this work is compelling and valuable only relative to biography; “this is a great achievement...for a person with a disability” is the most destructive and unfortunate possible understanding. This problem emerges in two distinct and passive ways: as an expression of a commonly held, inherent bias or an escape from the pressure of formulating a critical, thoughtful response. There tends to be a discomfort (even fear) that disability or mental illness elicits because the true nature of their difference is unknown - it remains a great and beautiful mystery. This mystery provides an unsure footing for the viewer, unable to feel (with either praise or criticism), if they understand and are receiving what's being communicated or that they’ll be exposed with their response. And so, the sympathetic eye is easily provoked and often may occur without provocation, or despite active attempts to dispel it in the nature of presentation.

installation view of Jessie Dunahoo's work at Andrew Edlin Gallery, image via Andrew Edlin Gallery. Dunahoo's installations are vehicles for relating his personal history and fictional narratives, while also recalling their genesis as a tool he devised as a child to navigate his family's farm in Kentucky.

In Nathaniel Rich’s recent piece about Creative Growth in The New York Times (A Training Ground for Untrained Artists), he quotes a 1993 article by Rosemary Dinnage in order to describe the appeal of outsider art: “The fantasy that over there, on the other side of the insanity barrier, is a freedom and passion and color that were renounced in childhood … the longing for a return to something direct and strong and primitive.” Dinnage, and Rich by reference, articulate a sympathetic bifurcation that is false; it’s implicated that mainstream contemporary art (we’ll refer to it as insider art) is inherently more structured and sophisticated (less primitive, less free). If this is understood in terms of biography, the real misconception becomes clear. It’s presumed that biography is important in outsider art and not insider art because the latter has a sophisticated, conceptual structure devised by the artist in the course of intentionally creating works of art (intended to be presented and marketed in the contemporary mainstream), a structure that references western art history and culture. In outsider art, a sympathetic viewer assumes that this sophistication is absent, so biography or a captivating narrative is necessary to take the place of a conceptual structure that provides its context. Thus, the perception is that an artist isn’t being intentional, but instead their disposition is what causes the work to be interesting.

In the presentation of Judith Scott’s Bound and Unbound at the Brooklyn Art Museum, curator Catherine Morris sought to avoid this characterization stating:

We have tried to resist viewing Scott’s lack of speech as a void in need of filling and instead have chosen to focus on what Scott does communicate through her work. Readings that draw on biography to construct narrative interpretations for artists who do not communicate through traditional means have historically taken precedence over other ways of understanding. This exhibition is, in part, an attempt to forefront readings of the work that ask questions without expecting definitive answers or metaphorical readings.

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/judith_scott/

Despite this earnest attempt to challenge the viewer to accept mystery, Cynthia Cruz, writing for Hyperallergic, responded “I question the importance of biography as it is emphasized in the wall texts. This results in silencing the work, turning it into the strange artifacts of a strange, not-understood person,” (Words Fall Away) suggesting that the mere presence of the artist's biography in the exhibition is sufficient to “silence” the artist's voice. Cruz makes a comparison to A Cosmos, at the New Museum, where Scott's work was exhibited without biographical information among insiders of similar sensibility. Certainly integrating works by artists with disabilities covertly into group shows with mainstream artists will effectively evade the sympathetic eye, but possibly at the cost of putting a ceiling on their careers and ultimately perpetuating the stigma that disability should remain hidden.

Daniel Green, Billy Ocean & Little Richard & Tina Turner, colored pencil/micron on paper, courtesy Creativity Explored

Beyond the problematic implications of both relying on biography too much or avoiding it altogether, often, actively excluding biography is a disservice to the work. David Pagel, in an excellent review of Helen Rae’s exhibition at The Good Luck Gallery (Exhibition Review: Helen Rae), creates an ideal balance of formal, conceptual, and biographical discussion. His criticism focuses primarily on the experience of viewing the work, with keen observations of her routine, artistic process, and unique way of seeing as they are relevant to her drawings, which ultimately assist in recognizing and appreciating their power.

Rejecting the presumption that outsider or visionary art is to be filtered solely through a biographical understanding, whereas contemporary art always speaks for itself, means accepting the fact that some elements of biography are important to all works of art. A heavy focus on biography is, of course, common in outsider art writing. Discussing his recent book about Martín Ramírez with Edward Gómez for Hyperallergic, Víctor M. Espinosa makes an important distinction between a sociological perspective and a formal one:

It is written from the point of view of someone who is practicing the sociology of art, not from that of a conventional art historian … Sociologists believe that no work of art stands alone like that. It’s not that simple. Various factors play roles in how a work of art is produced and, ultimately, in what it might mean at any given time — social, cultural, historical, economic and other factors.

HYPERALLERGIC

Traditionally, a sociological perspective (or even anthropological one) is permissible in the discussion of outsider art, but it’s not only to fill a void where the artist's own explanation is absent. Espinosa points out that absent any “sociological perspective” (ie. biography) the evaluation is incomplete. These factors are an unavoidable element of any work; certainly our knowledge of Kara Walker’s race or Jeff Koons’ marriage to Cicciolina, for example, informs our understanding of their work. As Matthew Higgs points out:

I think that that question of the artist’s biography is something that a lot of people have issue with in relation to outsider art. I was wondering why we don’t know more about the lives of contemporary artists, why it’s only when they suddenly get a 10-page profile in the New Yorker that we find out what their parents do. Unless an artist gets to a certain level of visibility, we know nothing really about a contemporary artist’s life. We don’t know about their home life, about their kids, what their kids do, what their parents did, or what their partner does. All of this is regarded as extraneous to the work, which of course it isn’t. It’s central to the work.

Artspace

Joe Zaldivar, Street Map of Claremont, California, marker on paper, courtesy of First Street Gallery

This begs the question, though, of what’s really occurring and why it's happening now, if outsiders and insiders are so similar in this regard. The real concern is not the presence of these ideas, but who controls them. Andrew Edlin Gallery’s Phillip March Jones explains the additional roles of an outsider art gallery director with Karen Rosenberg for Artspace:

Someone like Judith Scott … there’s a lot of reasons she wouldn’t be able to [market herself]. And other people are just so involved in the works they’re creating that it’s not really part of their reflective process. A lot of the art we show is created for very personal reasons, usually in private. Often, the artists create worlds they wish to inhabit. Maybe sometimes they don’t know that they aren’t inhabiting them—maybe they live within that work, or maybe the relationship to the work is more important, or real, than the relationships they have in our real world. I think someone like Henry Darger very clearly lived more in his work, his drawings, than in Chicago.

…As dealers in this field we have a greater responsibility to the artist, because frequently you are the one who is making a lot of the decisions that the artist would make. When I work with a contemporary artist, they’re present for the installation—they’re doing all these things that for the most part the outsider artist is not engaged in.

Artspace

What Jones is describing, in effect, is a process of translation. The trajectory of American art history over the past 100-150 years has been driven by a search for new concepts and divergent ways of thinking. This has always been most notably achieved by including ideas previously considered to reside in the margins - Picasso’s appropriation of the ideas and aesthetics of African art, the inclusion of women in the 60s and 70s, the appropriation of commercial and design aesthetics by Pop artists, current artists investigating race and LGBTQ issues, etc. This process has lead to a situation in which the boundaries of the creative culture are so thoroughly broken down that contemporary artists are expected to invent art for themselves and, in effect, become new outsiders. What remains of our consensus culture is only in the periphery - pristine white spaces, white cotton gloves, and expensive crates. Insider artists create for this context, but it’s social power has become equally available to objects like the quilts of Gees Bend, which once had a context and purpose of their own, if a curator such as Phillip March Jones is able to provide it.

Tom Sachs Space Program, image via tomsachs.org

Tom Sachs’ 2007 Space Program took place in the blue chip heart of the contemporary mainstream, Gagosian in Chelsea, but it’s only this context that makes it an insider work. Had he created the same body of work, but instead performed the landing in a midwestern backyard then he would be an outsider - and we may give greater credence to his stated goal of creating as a means of attaining the unattainable in a mystical sense, yet his social commentary most likely be dismissed and pathologized as an expression of some strange paranoid thought process. Those distinctions, however, are less important than the fact that it would still be a remarkable and highly sophisticated work. It is an important revelation that the difference between outsiders and insiders is actually just a few delicate details of circumstance. It’s not a desire to escape the superior sophistication of the mainstream that has lead to the inclusion of outsider work, but that the line between the two is increasingly blurred. From our perspective, these designattions have become obsolete and are more appropriately used in only a historical context.

Unfortunately, the sympathetic eye is almost inevitable and shouldn’t be the responsibility of galleries, curators, or art writers to actively target and discourage this tendency. It is their responsibility, however, to confidently lead by example in a full and fair engagement with the work of these artists as they would with any other, including uninhibited discussion of biography, disability, and the various relevant aspects of lifestyle and disposition that inform the work - a respectful practice of appreciating these works by approaching the unknown with wonder instead of fear. This may mean being comfortable experiencing a work as fiction when it was intended as non-fiction or recognizing that compelling, conceptual contrivances of a neurotypical artist may be just as compelling (or more compelling) as intuitive expressions from an artist with an intellectual disability. Because, by definition, neurodiversity will require communication across profound intellectual differences, including vast disparity in the fundamental nature of our experience - the work must become a point of connection without having to result in a consensus.

Marlon Mullen Update

Marlon Mullen, Untitled (P2403), acrylic on canvas, 36" x 36"

Marlon Mullen, Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 24" x 30"

Marlon Mullen, Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 30" x 30"

Marlon Mullen in the studio, images courtesy NIAD

Marlon Mullen (b. 1963 Rodeo, CA), who is now represented exclusively by JTT Gallery and Adams and Ollman, lives in Richmond California, where he maintains a studio practice at NIAD Art Center. Mullen’s process entails reducing found imagery, often in the form of art publications, to a point well beyond recognition. Mullen’s flat, simple abstractions are achieved with utter sincerity, devoid of stylistic embellishment, and without reverting to geometric or systematic deconstructions (calling to mind the work of Gary Hume or Monique Prieto). Each elegant, lushly painted composition feels like an original, unequivocal interpretation of its source (while maintaining mere fragments of the initial image), but ultimately asserting a new sense of resolution with power and charm.

Mullen has been exhibiting work for several years, but there has been a recent increase of interest in his oeuvre; after his inaugural show with JTT in New York, he went on to have a solo exhibition at Atlanta Contemporary; upcoming solo exhibitions are slated with Adams and Ollman in Portland, Oregon and Jack Fischer Gallery in San Francisco. JTT and Adams and Ollman will also be co-presenting a solo show of Mullen's work at the Outsider Art Fair in January.

In a March Artspace interview, on Finding Space in the Market for Underdogs, curator and White Columns Director Matthew Higgs asserted that Marlon Mullen is "an amazingly interesting painter...we did a solo with Mullen a few years ago...JTT saw his work with us and is doing a solo show with him now. I think that's a really amazing development, that Mullen's work, which was largely only seen in the context of the center where he worked, is now finding multiple audiences. Certainly, from our perspective at White Columns, the goal is to create an audience for these ideas - we're less concerned, or ultimately less interested, in creating a market for these ideas. But I accept entirely that sometimes a market will come."

Mullen's work was discussed more recently in a compelling article written by Brendan Greaves for Artnews, The Error of Margins: Vernacular Artists and the Mainstream Art World. Greaves investigates the current role of Mullen and comparable artists in the contemporary art market:

Though the art world may not yet have a satisfactory way of referring to artists like Mullen, who are variously described by such leaky terms as self-taught, outsider, and vernacular, it has, over the past few years, shown more interest in them and is gradually growing the existing market for their work. When this issue of ARTnews went to press, Christie’s was preparing a September sale of what it deems “outsider and folk art,” including work by such acknowledged masters as Chicago narrative artist Henry Darger, Tennessee stone carver William Edmondson, Swiss Art Brut exemplar Adolf Wölfli, and rural Idahoan James Castle, who made paper constructions and delicate drawings with soot and spit.

The anticipated sales prices of the vernacular works at the auction—ranging from $2,000 to $4,000 for small pieces by Clementine Hunter, a painter of life on the Louisiana plantation on which she lived, to $400,000 to $600,000 for a large double-sided Darger drawing—illustrate the highly variable nature of this still-developing market. As Cara Zimmerman, Christie’s newly hired specialist in the field, told me over the summer, “While some well-known artists like Darger and Edmondson have already achieved auction prices commensurate with post-war and contemporary artists, this is still a new venture for us.

Previous exhibitions include the Parking Lot Art Fair in San Francisco (2015), Welcome To My World at NIAD (2015), NADA Art Fair White Columns Booth in Miami (2014), Under Another Name, organized by Thomas J. Lax at the Studio Museum of Harlem (2014), Undercover Geniuses organized by Jan Moore at the Petaluma Arts Center (2013), Color and Form at Jack Fischer Gallery in San Francisco (2013), Marlon Mullen at White Columns in NYC (2012), After Shelley Duvall '72 at Maccarone in NYC (2011), and Create, curated by Matthew Higgs and Lawrence Rinder at the Berkeley Art Musueum (2011). Mullen is a 2015 recipient of the Wynn Newhouse Award and has work in the collections of The Studio Museum in Harlem, the Berkeley Art Museum, and MADMusée (Belgium). See more of Mullen's work here

Progressive Practices: The Basics

We’ve added a new section on the site for pieces of writing concerning the methodology of progressive art studios. We hope these will be a valuable resource to those involved in this work, as well as anyone interested in this emerging model for artist development. This piece, which discusses the basic, essential components of a progressive art studio, is the first of many. As always, your feedback is appreciated.

installation view of Judith Scott - Bound and Unbound, a recent exhibition at the Brooklyn Art Museum

“...there was an extraordinary amount of very strong and wonderful work coming out of these three studios…These centers, all three of which had been founded by the same couple, Florence and Elias Katz in the 1970s and 80s based on the same principles…I started to become intrigued by the question of why was there so much wonderful work coming out of these three art centers and was there something they had in common, some kind of methodology that was bringing forth such wonderful art…the methodology which was proposed by Florence and Elias Katz...which had to do with giving adult artists with developmental disabilities an opportunity to work in communal studios at hours which reflected the common work hours, five days a week 9-5, that these centers be connected to the art world, that there be a gallery connected to the studio, that there be not teachers but facilitators who would assist the artists in making their work, and that there would be a sales element.

It’s interesting that the first of these centers was created at

exactly the same moment of Roger Cardinal’s famous Outsider Art definition of

outsider artists being cut off from the world and these centers were radically

connected to the world...”

- Lawrence Rinder, Director of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, discussing the exhibition Create, which he co-curated with White Columns’ Matthew Higgs in 2011. You can view the full panel discussion “Insider Art: Recent Curatorial Approaches to Self-Taught Art” here

The Create exhibition in 2011 was inspired by the observation that the three Bay Area Katz-founded progressive art studios (Creative Growth, Creativity Explored, and NIAD) have been consistently creating high quality works and using a similar methodology, but without having much contact with each other (or studios elsewhere in the country) since their establishment. Our own research has found that this phenomenon isn’t limited to the Bay Area; studios have emerged across the country since deinstitutionalization began in the 70s - programs where incredible, valid art is created and whose methods include the same basic points. Although many progressive art studios have referred to the Bay Area programs as a development model, most were created prior to any knowledge of them.

The spontaneous, isolated development of progressive art studios throughout the world indicates something important and unique about what these programs are and what they mean. The insight to be gained is that a model of acceptance rather than assimilation is viable and incredibly valuable, if the culture is forward-thinking enough to accept it.

Whereas an assimilation methodology depends on developing a way of working with a person experiencing developmental disabilities that successfully produces the prescribed result (using contrived means to alter a way of being or behavior, to fit given expectations), the acceptance methodology begins with a perceived potential and conforms expectations to meet that potential with an open-ended concept of success. The acceptance model appears spontaneously because the potential identified, the creative person, exists universally. Conversely, the desired outcomes of assimilation methods depend on esoteric “best practices” informed by idealized or archaic concepts of behavior, professionalism, or generally appropriate ways of being.

Marlon Mullen, an exhibition currently on view at Atlanta Contemporary

As Lawrence Rinder points out, for the acceptance methodology of a progressive art studio to emerge and excel, it must simply operate on a handful of fundamental principles:

A radical connection to the world

Rinder references a radical connection, in direct contrast with Roger Cardinal’s definition of Outsider Art which is dependent on artists creating in isolation. A progressive art studio is also radically connected to the world in contrast with traditional services for people with developmental disabilities.

Offering integrated services has long been an ambition of service providers for this population. This is not only because of the proven efficacy of integration, as demonstrated by examples of integrated schools, but also for the sake of cultivating a more inclusive community. In adult life, (post-school) the concept of integration and inclusion is far more complex; everyday life can not be simply “mainstreamed” the way that a school is. Progressive art studios provide opportunities for powerful forms of integration and inclusion that aren’t possible in any other form of support. Successful fine artists such as Judith Scott, Dan Miller, and Marlon Mullen (all of whom have been supported by progressive art studios) are the first examples of people receiving supported employment services who are internationally competitive and influential in their field.

This radical connection depends on the involvement of those at every level of the program who are personally invested in the practice of art-making. The work of facilitators and management must be informed by their knowledge of and personal investment in art (in the context of contemporary international and local culture, as well as art history). Employing fine artists as facilitators and studio managers also allows a connection to develop on a more fundamental level, in the peer relationships between artists in the studio (abstract of being on the providing or receiving end of services). This, in conjunction with the exhibition of artwork, offers unprecedented visibility and presence in the community, culminating in the best possible conditions for the development of genuine professional and personal relationships with other artists who are not paid supports.

Nicole Appel, Animal Eyes and Russian Boxes, colored pencil on paper, 19″ x 24″, 2014, Pure Vision Arts, NYC

Investment of time

Artists having access to the studio and utilizing it for periods similar to regular work hours is extremely important. This point is a matter of principle and a good vehicle for advocacy of the progressive art studio model as a whole.

Often, those involved in making decisions by committee with or on behalf of a person with a developmental disability (including parents, case workers, service coordinators, counselors, and other members of the “support team” who are not artists) will oppose large investments of time in the art studio. This occurs for the same reasons that parents oppose children pursuing artistic careers, schools persistently cut art programs, or illustrators, designers, etc. must argue the details of invoices with clients. Creative work as a valuable professional discipline is stigmatized as frivolous throughout american culture, and pushing for higher investments of time is the front line on which these studios combat this stigma. Although it takes place in a congregated and specialized setting, the progressive art studio is much like a job coaching service for those pursuing serious careers as fine artists.

Schedules should range from 6-8 hours per day and 2-5 days per week depending on how developed the artist is, what other employment services or opportunities they’re engaged in, and how much time they want or need to spend working on art. Generally speaking, artists should be permitted to commit as much time as they want to art-making and should be encouraged to commit as much time as they’re able.

Project Onward's studio space in Chicago

An open studio

The studio must be a space belonging to the artists that’s conducive to creative work, where artists gather to maintain studio practices (not unlike a group of like-minded individuals in any workplace). The concept of the artists owning the space is crucial; providing opportunities for people experiencing developmental disabilities to create art is far more common than actual studios are, and this idea is one of the key distinctions of an approach that’s truly progressive.

There’s an obvious, superficial transition that can be made from a traditional day habilitation program to a shared art studio space. Both are fairly open workspaces where individuals exert themselves productively; several existing studios were once day hab programs or still operate under the pretense of being so in the eyes of Medicaid. However, even if a day hab program shifts its focus completely to art-making and physically becomes an art studio, it’s not a progressive art studio until it achieves a complete conceptual shift of paradigm. The space must be one in which the artists are free to invent and strive to meet expectations of their own devising, not a space where they’re guided to meet the expectations of staff. Any intensive one-on-one, step-by-step directions, or didactic practices must be eliminated. The goal of a progressive art studio is not to provide therapy, education, or any influence of assimilation - it’s to validate an artist’s experience and foster the capacity to share that experience on their own terms.

It’s not necessarily the case, however, that a progressive art studio completely lacks an educational element. For studios that don’t have a limited admission with portfolio review, there’s a large group of new artists working in the studio who benefit from significant initial guidance in order to discover art-making and learn to value it. Also, the studio may need to set boundaries regarding the use of shared materials and it’s important all people using the space conduct themselves in a professional manner respectful of a communal work environment. This should be achieved with guidance and assistance as needed. Ultimately, though, the core goal must always be total creative independence.

installation view at DAC Gallery in LA

A gallery and sales element

The gallery and sales element of the progressive art studio provides at least two essential functions. Firstly, as discussed above, exhibitions of artwork are a powerful form of integration into the community that’s not available by any other means. Even in cases where the artists don’t share a physical work space with other artists who aren’t paid supports, their presence and visibility in the community through a gallery show fosters connections with other artists and the general public on the artist’s terms.

Secondly, the handling and display of the work in a fine art exhibition space allows the studio to set an important example in the community for valuing the ideas and experiences of those living with developmental disabilities. By handling and installing the work professionally and making a meaningful investment of space and time in the gallery, the program makes a profound statement about the value of the artist, their ideas, and voice.

Conversely, handling the work in a manner divergent from accepted standards of a professional artist, ie. overcrowded salon style shows, improperly installed or framed work, or uncritical exhibition of unsuccessful/unresolved works, makes the opposite statement about the work and artists, effectively presenting the work as other and lesser. Allen Terrell, Director of the ECF art centers and affiliated DAC gallery (one of the most professional gallery spaces directly affiliated with a progressive art studio) is driven by a simple principle: don't do anything with the artists’ work that you wouldn't do with your own.

Yasmin Arshad

Untitled, marker on paper, 22" x 30"

129999, marker on paper, 22" x 30"

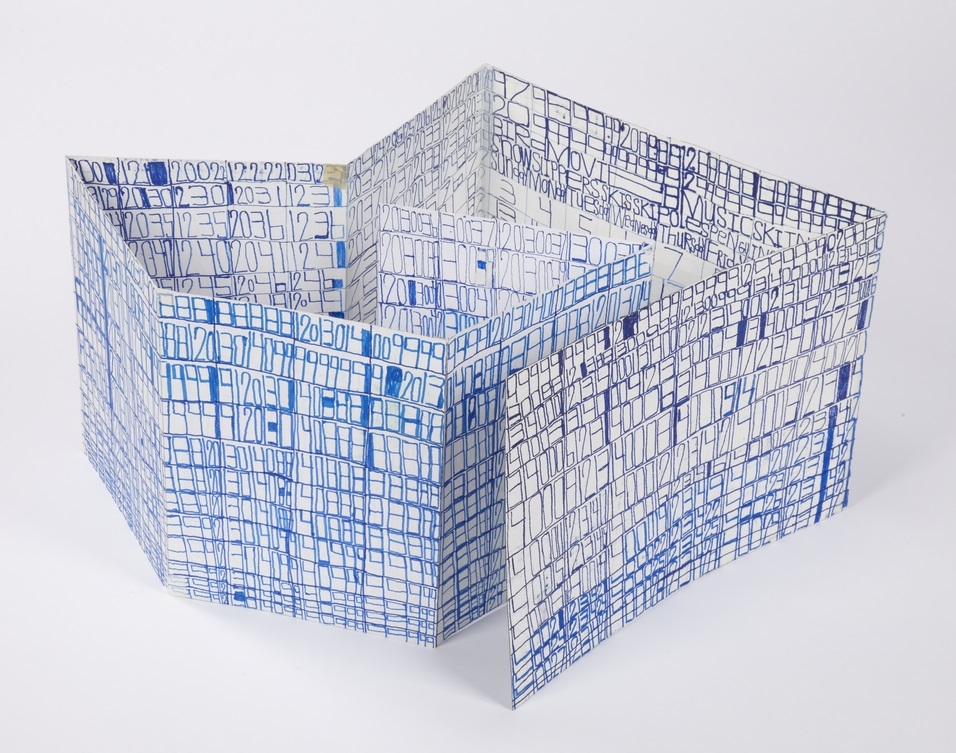

Untitled, marker and acrylic on wood, 19.5" x 19.5"

Untitled, marker on paper, images courtesy Gateway Arts

Arshad’s distinctive works are characterized by series of numbers, phrases, and concepts of time that manifest in the form of visual and spacial poetry. An investigation of the overlap in the process of seeing and reading akin to Christopher Wool is present - where Wool employs the arrangement of words on a surface to disrupt the reading process systematically, Arshad’s visual and written languages instead merge more fluidly. Text forms, influenced by dynamics of color and scale, impose elusive and subjective variation in the reading experience.

Arshad’s work reflects an avid interest in ideas related to the passage of time. An invented symbol for eternity, 129999 (a single number indicating all months and years), often surfaces in her work; she also lists years chronologically beginning with the year 2000, organizing the numerical information into multi-colored grids. Over the course of 46 years, Roman Opalka painted horizontal rows of consecutive, ascending numbers (1 – ∞), an ongoing series that ultimately spanned 233 uniformly sized canvases. In “Roman Opalka’s Numerical Destiny” for Hyperallergic Robert C. Morgan writes:

From the day his project began in Poland until his death in the south of France in 2011, Opalka combined clear conceptual thinking with painterly materials. His search for infinity through painting became a form of phenomenology, which, in retrospect, might be seen as parallel to the philosophy of Hegel. Through his attention to a paradoxically complex, reductive manner of painting, Opalka focused on infinite possibilities latent within his project.

Arshad’s rigorous, repetitive approach is similar to 0palka’s engagement with infinity, yet there are more prevalent breaches in her pattern-based system. Much like the process of weaving, Arshad’s drawings reflect an intrinsic structure that serves as a guide for intended visual results, yet there is room for distortion and a spontaneous response to the surface.

Arshad (b. 1975, Florence, Italy) has exhibited previously at Cooper Union (NYC), the Outsider Art Fair, The Museum of Everything (London), Phoenix Gallery (NYC), Berenberg Gallery (Boston), Trustman Gallery (Simmons College, Boston), Drive-By Projects (Watertown, MA), Creativity Explored (San Francisco), and at Gateway’s Gallery in Brookline, Massachusetts. Arshad lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts and has attended Gateway Arts’ studio since 1996.

see more work by Arshad here

Visionaries and Voices

Established 2003, Cincinnati Ohio

The Visionaries and Voices Northside Studio Building in Cincinnati, featuring a mural of local legend Raymond Thundersky

Ohio has a high concentration of quality progressive art studios compared to other states - 12 in 11 different cities across the state. During our research trip, we were able to visit both Visionaries and Voices (V+V) studio locations in Cincinnati. V+V embodies all of the essential qualities of a progressive art studio, providing two fine art open studio spaces that are utilized by more than 140 Cincinnati-based artists experiencing developmental disabilities. The studios are staffed by trained artists who provide non-intrusive guidance and facilitation, and the Northside location includes a professional exhibition space.

We spoke with Tri-County Studio Coordinator, Megan Miller and the Northside Studio Coordinator Theo Bogen during our visits; both are dedicated to and passionate about the mission of V+V and committed to facilitating the studio process based on what each artist is compelled to make.

an artist's work space in the studio

V+V stands out because of its professional, egalitarian culture. The relationship of the staff to the artists in progressive art studios is often simplified in terms of teaching or facilitating. In practice, the latter is defined by hands-off assistance, allowing the artist to create freely, and the former is a more codependent or antiquated approach defined by teaching or instructing in a didactic sense. V+V not only demonstrates the more progressive approach, but also in a deeper way, shows that this bifurcation is just a piece of a more complex continuum. Artists at V+V work with not only a sense of ownership of their own practice and work, but also with ownership of the entire enterprise, the studio itself. They move freely throughout it, develop personalized workspaces with ongoing projects and materials, and enjoy a peer relationship with the assisting staff.

This culture may be explained by their unique history. The studio began as a work space for the late Raymond Thundersky (now a local legend), and slowly transitioned into a non-profit program over the years. The workspace was organized by a couple of social workers for Thundersky and a few other artists. The identity of the studio as a workspace provided wholey to a group of artists, as opposed to an art program functioning as a service provider, persists in the culture today, much to their benefit. Most prospective artists hear about the V+V by word of mouth and have an informal artist interview to determine if they’re a good fit for the studio. Ultimately, their admission is dependent primarily on whether they’re interested in working productively as an artist. To be productive, though, is not considered to be synonymous with being prolific, as many artists may be productively and creatively engaged without necessarily producing commercially viable or permanent works.

V+V's exhibition space

The V+V gallery usually hosts five exhibitions a year, and organizes exceptional group shows. They typically curate thoughtful exhibitions featuring 2 or 3 of their artists in a manner driven by those artists’ ideas. Sometimes artists function as curators as well. Furthermore, exhibition opportunities for artists’ work are sought out at galleries, museums, universities, and other venues on both a local and national level. In addition, a Teaching Artist Program (TAP) is offered as an option for artists that instead have an interest in pursuing visual art careers in teaching, speaking, and other leadership roles. TAP “supports those goals, while offering the community the opportunity to learn about art from a unique perspective. V+V artists who complete TAP courses bring lesson plans to classrooms, community centers, and partnering organizations all over greater Cincinnati. Each artist develops their own lesson plans customized to benefit students of all ages and abilities.”

a portion of the inventory stored at the Northside Studio.

Chris Mason